Video summary:

In June of 2019 I went to the doctor for a check-up.

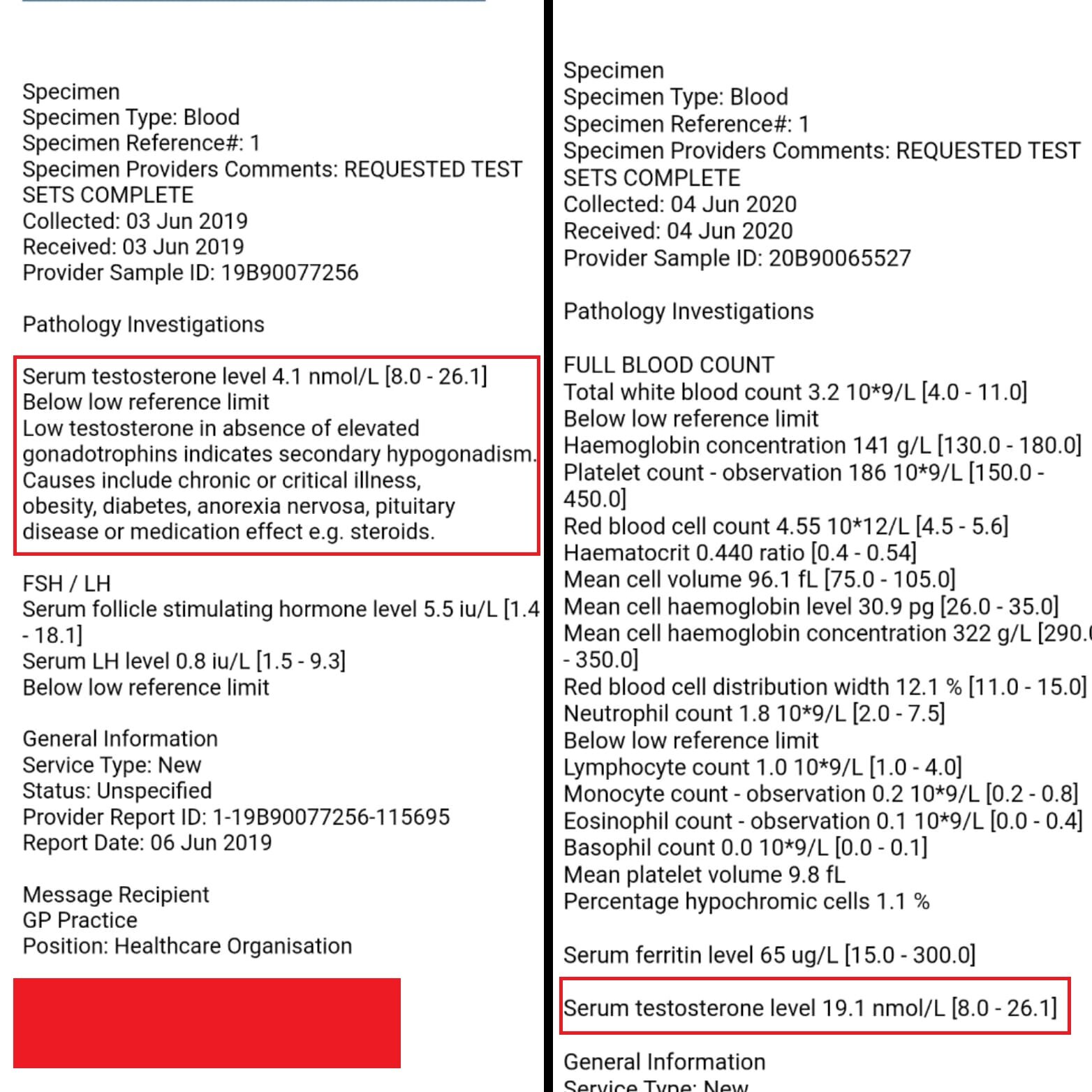

I had experienced low libido for a while and wanted to make sure nothing was amiss. To my surprise, my blood tests showed I had less than 1/3rd the testosterone of a 70 year old man, along with other alarming results.

So extreme were these test results that I had an MRI on my brain to confirm there wasn’t a tumour growing in there causing all of this.

Ultimately the diagnosis was Exercised-Induced Hypogonadism.

This basically means that, through brutalising my body by training too much and not eating enough, I had caused it to shut down certain hormone productions, including Testosterone, LH and so on.

The diagnosis forced me to come to terms with the fact that I had developed not only an exercise addiction, but an eating disorder. During that time, and for years prior, I had followed a pattern of intermittent-fasting to obsessive levels. I was sometimes going 40+ hours without eating, all in the name of ‘health’. I trained almost every day, sometimes twice a day. There was no such thing as ‘enough’ training.

The diagnosis was a serious wake up call. I had to make some changes.

This is a follow-up from my initial post a year ago.

In the year since, I have improved immensely:

My blood tests are now all normal, and within healthy ranges.

I’m training much more sustainably, doing a healthy mix of cardio, strength training and stretching.

I’m eating at regular times, not calorie counting, and not going days without food. I'm not fasting.

I’m much, much happier.

Oh, and my libido is back with a vengeance, with my testosterone nearly five times higher than a year ago.

Ultimately - I’m back to being myself.

In this post I detail my recovery journey these last 12 months. Following that, I’m going to go into detail around the changes I made - both physical and psychological - which have helped me get better.

Once again - my hope with this post is the same as it was with the previous one - if you’re someone who has some of these issues, perhaps my story will help you - either to talk about it, seek professional help, or just give you some ideas which might help you on your journey of recovery.

This is what helped me.

The initial test, and the one a year and a day later. 4.1 nmol/L to 19.1 nmol/L

The Macro: What happened in the year since

Immediate reaction:

The response to my initial post was incredible, if a little overwhelming.

Firstly; the amount of support I received from friends and strangers was truly moving, and it made me immediately glad that I had shared my story. It was very freeing to be able to talk about what I was dealing with so openly.

However, what I didn’t at all expect was how many people would contact me saying that they could relate to my experience directly.

Most often, this was due to experience with an eating disorder, but some also had, at one time, an exercise addiction. This ranged from acquaintances whom I had met in passing, to old friends, to complete strangers on the internet. A great deal of people had suffered through something similar and wrote to me about it.

What was even more surprising were the people I knew who reached out, most of whom I never could have previously imagined would have had similar problems.

A small hope of mine was to just open up about my struggles, such that maybe someone who had been in my position pre-diagnosis could recognise themselves in my reflection. What I got in response was a realisation that eating disorders are, (at least anecdotally to my circles) horrifically common.

So to you reading this - if you’ve ever struggled in your relationship to food, I think you’d be surprised at how others could relate to your experiences.

Though there were a smattering of responses I didn’t quite expect. One person told me their post made them feel worse about themselves, which I was torn up over for a while. Another, in a total reversal, actually complimented me on how good I looked in my starvation-mode pictures. Some might’ve taken offence to this – but, in reality, I appreciated the person for their honesty.

It’s true. By conventional fitness-model like standards, I did look ‘good’ in those photos. This is because the fitness industry isn’t about fitness - it’s about aesethetics. A toned physique is a common – but not an absolute – byproduct of being incredibly fit, or being an athlete. We mistake a possible side effect - looking lean - for the real thing - being fit and healthy.

Coincidentally, a few days after I published my post, an athlete I admired and had written about before Amelia Boone came out with a post detailing her own eating disorder.

It was kind of crazy to me that someone who I thought was a total badass had a similar problem of breaking themselves (albeit, at a much higher athletic level)

Ultimately one thing was seared into my brain - I felt I had been a bit brainwashed, much like millions are, into thinking I had to achieve a fashionable body type which represented health, and proved you worked hard in the gym.

I needed to undo this programming, fix my mind and my body, and get my balls back.

So - I decided with immediate effect I was no longer going to fast and could only exercise 3-4 times a week.

July-September

These were tough months. I definitely got worse before I got better.

I stopped ‘training’ altogether. At the limit of 3-4 times a week for exercise, given I had previously relied upon it daily for emotional stability, it was felt as a drastic cut.

Days where I didn’t exercise I had depressive bouts, perhaps akin to some sort of withdrawal.

I felt useless and weak. I put on a few kilos just from gorging myself regularly at meals - I had forgotten how to eat like a regular person. My body was probably thankful for it, but mentally I was not. I took a vacation with my family to Turkey to get some sun, and just hated the lethargy of lying around, doing nothing. I hated how I looked in photos as well.

Reality

Perhaps bizarrely, I still felt a lot of shame about the problems I was experiencing, despite having written about them online in extensive detail.

Case in point: After my holiday when I returned to work, I found myself in an uncomfortable situation regularly. On a daily basis I would receive snarky comments for a certain protein-porridge mixture I would make daily in the microwave. Telling my colleagues “hey, I’m trying to eat the same thing every day and this is a meal that I feel comfortable with” didn’t feel like something I could say. They weren’t aware of my issues, and I don’t think had any bad intent, it was just hard.

In many ways, talking about this online was, to me, a lot easier than in person.

It remains that way.

Anyway, for entirely unrelated reasons, I started looking for another job.

Other significant actions: I invested in an Oura ring - a sleep tracker, to see how well I slept. Turns out, terribly. I set out to fix that too, figuring it could only help.

Otherwise, I tried to keep other aspects of my life the same. I kept doing improv, I kept seeing friends, I just tried to stop my destructive habits.

It sucked. It was necessary.

October-December

In October I started a new job, at the company where I’m currently working. It’s the best job I’ve had to date, so it was a huge step up in terms of happiness and life quality.

At the same time, I was starting to make some headway with exercising in a way that didn’t wreck me - getting more into cardio workouts. I adjusted my strength training to be more ‘hypertrophy’ focused (fewer crazy positions on the rings, more just trying to get blood pumping through my muscles).

Basically for those who aren’t into fitness - building muscle and getting stronger are two related, but separate goals. Gymnasts aren’t huge but are very strong due to a combination of muscle, tendon, ligament strength and so on. Bodybuilders are huge and strong in a different capacity.

Previously I had been training for gymnastic strength - focusing on very high-intensity stressful positions on the gymnastic rings. I would do moves for sets of 1-5 repetitions. This is extremely taxing on the nervous system, as you’re sort of going ‘all-out’ for 10-20 seconds at a time.

Bodybuilding style training, or ‘hypertrophy’ training, typically involves sets of 8-12 repetitions minimum, for sets of 30+ seconds. So you’re working at a lower intensity, which is obviously still taxing, but in a different way. - often good in strict isolation movements.

Neither is ‘better’ - both can be wonderful for the body. I hadn’t ever really tried to pack on any muscle size before, so I figured I might as well explore other training methods while I was on a sabbatical from training intensely.

My weight plateaued, and I started feeling happier. Depressive episodes from not training became less frequent. I was slowly sleeping better.

I was on the mend.

January-March 2020

The trend of improving continued.

I started feeling ambitious for my training once more so began a training program to try and finally get the One Arm Chinup. I got very close.

My new job had me travelling a lot, which interfered with sleep quite a bit, but I still managed to make ‘sleep gains’.

I was still regimented with my food intake, but was slowly becoming more relaxed at the prospect of a random meal which I hadn’t prepared myself.

I was still getting happier.

March-Now

Isolation, for me, brought a lot of benefits health wise. My normal commute to work was 1 hour each way. Much like many people working in the city, this extra time in quarantine, while partially filled with extra work, was not entirely so. I liked this.

Gyms closing meant I went ‘back to my roots’ training wise - bodyweight training. Lots of pullups, pushups etc. I loved it.

I also started growing out my patchy hair as the sun started returning, and found that, to my surprise, my hair was a hell of a lot thicker than it had ever been.

I booked a follow-up blood test towards the end of May, and, well, here we are.

The Micro: Strategies and Tactics for Recovery

In brief, the Gonad Rehabilitation Programme was simple:

Months 0-6: train less (when you do train, do cardio), reduce stress, eat more, sleep as much as you can. Repeat.

Months 6-12: train in a more varied way (more cardio), minimise stress, eat more, sleep as much as you can.

The specifics:

Eating

So the situation for me was the following - I had negative thought patterns in my head, and they weren’t going to go away overnight. I was worried about getting fat, but simultaneously didn’t want to be weak, etc. I also needed to stop calorie counting. Anyone who has obsessively counted calories knows that it’s hard to stop. Every food you look at, you’re checking the label or if not, doing an approximation in your head. I needed to find a way of eating that was sustainable, promoted good thought patterns, but didn’t create a mental battle every time I ate.

So I decided to eat to satiety - but cleverly.

Eating low calorie dense/high satiety foods - By switching to just following my gut, I wanted to use foods which erred on the side of telling me I was full rather than the opposite. So I focused on foods which were high in satiety but relatively low in caloric density (and also healthy). This meant lots of fruit and vegetables, and my go to - popcorn (air fried). If I ‘overate’ then the ‘damage’ would be minimal. I gradually extended this to other more calorically dense foods as time went by, and now I don’t think about it.

Though I have developed a bit of a popcorn addiction. I consider this an upgrade.

I’m not joking. This is a 9kg tub of popcorn kernels. I’ve refilled it more than once.

Eat set meals, regularly - I would have the same meal regularly on certain days. Once I established some meals that mentally ticked my hunger box, and I knew made me feel good, I could default to these and stopped thinking about food altogether, thereby, in the short term, solving the problem.

When in doubt, more yoghurt

PLAN OF ACTION:

Eat satiating foods

For me, this meant eating primarily low-calorie dense, ideally high protein and fibre, high volume foods.

Hit 1g of protein per lb of bodyweight (or 2.2 grams per kg per day). This is good for both muscle recovery and sateity

Have 10-20 set, go-to meals. Prepare these. Have these at the same time every day.

Eat at regular times. No more fasting.

No calorie counting

Eat more if you need to eat more.

Training

Oh boy.

To be honest, the long and short of this is “do less” but not “do none”.

As I wrote nearly a year earlier, unlike alcoholism, the optimal solution to exercise addiction isn’t (I don’t think) to stop training altogether. I mean, we have to move, and exercise in the right dosage is one of the best things you can do for your health.

To begin with, I drastically cut back. I started doing a lot more cardio, which I found benefited me mentally if nothing else. Throwing this in, and ultimately doing some less intense strength training, meant I was never taxing any particular energy system/part of my body too much.

Another crucial addition to my approach was the back off week. I got this idea from Jujimufu. It’s revolutionary. When you feel fatigued, and your performance drops after a few sessions, and you’re tired, rather than getting depressed and fasting and trying to go harder just stop and don’t train for 5-15 days.

This was hard to do. I still don’t like doing it. But, you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do.

If you’re interested in overtraining/getting a bit more of a balanced view into training than just BUILD MORE MUSCLE BRO I thoroughly recommend checking out The Big Book Of Endurance Training by Dr Philip Maffetone - it’s the best bit of material on overtraining I’ve found in the dozens of books I’ve read on the subject, and that’s just one chapter!

LESS OF THIS

MORE OF THIS

PLAN OF ACTION:

At first, cut down the volume massively. No more ‘training’. 3-4 exercise sessions a week

No more intense strength training. Start doing some cardio. Variety is the key.

As aerobic fitness improves, slowly, slowly start adding some strength and flexibility training

Find a nice balance

RECOVER AS HARD AS YOU TRAIN - take back off weeks!

And to those wondering - as I would be - how do I look now, physique wise? While it’s not something I care about so much, it’s something I would have cared about a year ago. So, if you’re interested, check out the video around the 21 minute mark.

Sleeping

As I mentioned, I invested in a fancy sleep tracker - an Oura ring - which basically told me what I suspected, I suck at sleep.

Let me clarify - I was in bed 8 hours a night most nights - I was a very good boy

But a lot of that time I wasn’t actually sleeping. I would wake up in the night constantly from nightmares and the like, and sometimes take an age to get back to sleep. Plus, sometimes it took me an hour just to drift off.

So the reality was that, at the start of my rehab journey, despite trying to get more sleep than ever, I averaged between 6.5 - 6.75 hours of sleep a night.

My goal was to get 8 hours a night. I’m still not there, but I’m getting closer.

My approach was twofold - increase sleep efficiency (how much time I’m in bed and actually asleep) and increase the amount of time I’m just in bed.

Honestly, I’ve had mixed luck with the former. For a while it just seemed my body didn’t care how ‘relaxed’ I was before I went to bed, I would only be asleep a certain fraction of the time I spent horizontal. Only recently has the needle shifted there.

The latter worked well, but was a pain. Spending 9.5 hours in bed, knowing you’ll be lucky to be asleep for 7.5 of those is arguably a poor deal, but it’s one I knew I needed to make.

Sleep GAINS

PLAN OF ACTION:

Find a way to track your sleep. Systematic errors are likely consistent - an upward trend in sleep time/quality is likely accurate.

Prioritise it ruthlessly

Do all the sensible things (less screen time before bed, same bed time, wind down routine etc)

When insomnia strikes, don’t panic, accept it, in the course of a year or a lifetime, it is but one night.

The Mental Game

This one is useless without the others.

By changing my habits, I changed my thoughts directly. My recovery wasn’t done sitting in a full lotus, it was through small decisions daily. By adopting new habits, I was adopting new ways of thinking.

To do this, I began cutting off some toxic people in my life. I needed the energy to deal with my own bullshit for a while.

Secondly, I went back to therapy. Previously I had been for problems with depression, and it had helped enormously. What’s the point of having a busy city job if it can’t fund your therapy to cure the stress from said job?

I had to remind myself daily, almost like mental repititions, of certain things. Food is fuel. I need to recover etc. In particular, watching Greg Doucette videos weekly helped enormously with this. He’s a 46 year old Canadian bodybuilder, who has competed 40+ times. He’s dieted down time and time again. He knows hunger better than most athletes. He’s been there, and he knows how to deal with it. His positive attidue, and pragmatic approach regarding fitness, diet and hunger were profoundly influential to me during this time. See some ‘natty or not’ videos, or videos on binge eating etc.

He’s certainly an acquired taste, but medicine is seldom sweet.

Ultimately, I think my mind followed my actions more than the reverse. The main mental move was made at the start - change my habits, to get better, even if it sucks and is unpleasant. Rebuilding a more positive attitude to food, training, and my body image have all been secondary to the aforementioned actions. I’m only competing with me, trying to be the best I can be. If I don’t fit the aesthetic standard, well hey, there are worse things to happen in life.

PLAN OF ACTION:

Cut out toxic people

Discover any related issues you might have - why do you behave this way. Find those issues. Face them.

Remind yourself that

Food is nourishing. Food is fuel. Food is good!

You need to recover as hard as you train

Don’t compare your body to anyone elses. Be the best you can be - there are some serious incredible genes out there, don’t compare yourself to them.

Training is something you get to do, not something you have to do

Suffering does not make you strong, or better. Sometimes suffering is just dumb.

Ultimately, training/eating should give you more than you give them - if you’re really in control, you wouldn’t obsess over either

Surround yourself with positivity. There is a way.

Now

I don’t think about food much anymore. I’m not looking for a crazy new diet to optimise my health. I eat lots of vegetables and fruit, meat fish and dairy. The only thing I focus on really is eating enough protein.

I do a variety of workouts - training is fun again. I’m playing around with methodologies and programmes. It’s got me through quarantine and the anxiety about the world melting. It’s helping me, not hurting me.

I like my body. I listen to it. I rest when I need to.

I sleep better. I wake up in the night less, and get to sleep easier.

For the time being, this whole thing seems to be working for me. I’m going to get another blood test in a few months, and see if the needle shifts any more. Who knows, I may not still be fully recovered. It’s entirely possible I was wrecking myself for 2+ years (as detailed in my last post). It’ll likely take more than 12 months of good behaviour to repair the damage.

But I’m on the mend.

I’m hugely grateful to all my friends, and my family, for putting up with my bullshit and keeping me sane throughout this time. Thanks for sticking with me.

Turns out testosterone helps you grow facial hair. Also, my head hair seems to be thicker than it was before - I’ve definitely not regrown hair follicles, but it’s super interesting to me how thick it is now!

Final Thoughts

The hardest few months were the first three. After that, as I felt happier and better, things became easier. There were definitely still low moments, the odd binge, the odd urge to fast, the odd manic compulsion to train, but these all slowly became less frequent and subsided as I found my balance.

I turned 26 back in May, and for my birthday, my sister made me this card.

When I saw it, it clicked.

I’m back.

I’m no doctor or expert on these things, but if I met you, I’d say this:

It can be done. You can come back too.

And if you’re reading this, and you can relate to these issues, I hope you do.