I went to the doctor for a simple reason; I had zero libido.

For the past 6 months I haven’t really been dating, nor had any real interest in doing so. When I did find myself on a date, or something approximating one, I found I was never really feeling it.

Psychologically, I told myself I was just on sabbatical from the dating scene; I’d had enough of that in my life for the moment and I was, for now, focusing on other things.

However, at a certain point occurred to me that it was suspicious that I didn’t find anyone attractive, in any sort of carnal/primal sense. The common denominator to this situation was, ultimately, me, not other people.

I’m a health conscious person - actually, I’m pretty health-obsessed. I consume a huge amount of information on the topic. I’m very careful about my diet, meticulous about getting enough sleep and I exercise relentlessly. So I didn’t think there was likely to be anything wrong with me. After all, I must be super healthy — right? Despite this, it made sense to get a check up.

After informing my GP of my lack of carnal urges, he echoed my concern and organised a blood test to investigate.

The results were both alarming and surprising.

The wake up call moment.

And yes, I have since been told I had this on backwards.

My red and white blood cell counts, lymphocytes, LH and testosterone were all extremely low – well outside normal range. My testosterone level was not merely low, it was diabolically so. I had about 1/3rd the expected testosterone of a 70 year old man. My LH wasn’t far behind, with some other random red flags in other categories to do with liver and kidney function. The results were so bad that I was booked in for an MRI on my brain, as these are the kind of markers that can come from having an unwanted growth on the pituitary gland, or something interfering directly with the hypothalamus.

Thankfully, my brain scan came back with ‘no significant abnormalities’. Until that point, I had been living for a few days with possibilities that included some kinds of brain growth, and or/leukaemia.

Instead, my diagnosis was Exercise-Induced Hypogonadism

This is a condition which basically means I’ve overworked my body through a combination of exercise and general stress to the point where my pituitary gland and hypothalamus are in semi-permanent fight-or-flight mode. I.e. non-vital functions like testosterone production and other hormones have been greatly attenuated. Other symptoms of this condition, besides the obvious testosterone markers, include chronic fatigue, mood swings, and a whole host of generally debilitating experiences.

This condition currently doesn’t have a lot of research on it, though some is emerging from studies being done on male ballet dancers.

A similar condition that is far better understood, however, occurs in some female athletes. This is called Hypothalamic Amenorrhea.

When the body fat % of these athletes gets too low, combined with their extremely gruelling training schedule, they experience hormone disruption - they lose their period. Because of this symptom, it can be easy to diagnose (though other related symptoms include chronic fatigue, extreme hunger, feeling cold all the time and so on).

In men, there is no such explicit tell for our hormones being out of balance, which means Exercise Induced Hypogonadism is harder to diagnose.

Luckily, the condition is highly reversible and simply treated; exercise less, eat more, and learn to god-damn chill.

To say this was a wake-up call is an understatement. I had a whole series of narratives about health - both personally and generally - shattered by this revelation. It forced me to confront a lot of tendencies and obsessive behaviours I’d been cultivating over the years, and reevaluate them.

The following post is about how I, rather stupidly, let things get to this point.

It’s about self-medicating with exercise: it’s about obsessions turning into addiction: it’s about body image: it’s about eating disorders: and it’s about what I’ve dubbed my ‘Gonad Rehabilitation Programme’ (GRP).

My hope is that if someone out there is in a similar position to me, or is nearing it unknowingly, this post might act as a red flag or serve as your wake-up call. I told my GP I was thinking of writing about this, and he encouraged me to do so, believing that there’s a real possibility that my condition is much more common than is currently known (partly because it’s hard to spot, and partly because young men are less likely to talk about a drop in their libido).

EDIT JUNE 2020: Since writing this post, I made some lifestyle changes (detailed at the end) and wrote a one-year update here

How this began - September 2016

My physique, August 2016, before all this started. I was 80kg.

I first started to use exercise as a mood-booster/antidepressant towards the end of 2016. I had been exercising regularly before then but it was always strictly a hobby. This was the first time in my life when I began to use exercise as a psychological crutch.

My first job out of university had me travelling around the country for work and I ended up spending most of my first 7 months at a client site away from home 4 days a week.

While this was going on, I fell into anxiety and a mild depression, for a variety of reasons including general worries about the future, relationship concerns and loneliness.

Next to the office was a gym – a really great gym. Within my first few days at this location I established a routine whereby I’d head there straight after work, and work out for an hour or so.

I would always feel better afterwards.

One day, a few weeks in, it occurred to me that I could probably fit in a quick session at lunch - maybe only 20-30 minutes, but it’d be better than nothing. Given I had made no real effort to make friends there, I felt I had nothing better to do, so soon I would routinely find myself heading to the gym during the day, and then again in the evenings.

Some months later still, I made friends with an enthusiastic and highly accomplished ultra-marathon runner who would train at the gym before work. So some days I would go before work too, and then again at lunch, and perhaps again after work. My schedule evolved to what you see below.

(Obviously, this schedule, and all the ones you’ll see in this post, are my ‘extra-curricular’ schedules. I did go to work, I promise).

I would spend 3-4 nights out of London, a night or two in London, and a night or two in Cambridge. Rinse and repeat.

Sessions: between 4 and 8. Total time training a week: 4-6 hours.

After I started working in London regularly, I switched to a more moderate once-or-twice per day schedule 4-5 days a week, usually taking the weekends off to go to Cambridge. But I was still training a ridiculous amount, and without much direction. I didn’t have a coach – I was only going off of what I had read in books, and from reading about various athletes I admired.

These all read ‘train’ because I didn’t really have much of a programme. I would show up and just work hard on something

Sessions a week: between 5 and 7

Total time training a week: 5-6 hours.

During this period of my life, when I was down and depressed, exercise kept me afloat. It was the one reliable thing that improved my day, every day. It just made me feel better, it was that simple.

And so I gradually did more and more.

October 2017 to June 2018

The following year of my life - October 2017, to June 2018 - I found myself at Oxford University. I was going to be there for about a year, doing a Masters in the Philosophy of Physics.

Right at the start of this period was the first time I’d been prescribed some sort of actual medication for my anxiety and depression. This was done just before I moved to Oxford. I ended up never using this prescription, mainly because I figured that a change of environment might serve to help my symptoms enough on its own. I ended up having some counselling, which I’ve written about before here. Strangely enough, however, my exercise and training was never really discussed. I expect it’s because, at the time, I only saw it as a positive, so I didn’t think to bring it up.

Ultimately, the change of environment, and new lifestyle, definitely helped.

However, the fact that I now had a lot of free time, and full access to a college gym, meant I could now train as much as I wanted. Naturally, I was soon going first thing every day - usually 6 days a week for 60-90 minutes. On Sundays, I would do sprint training, or go for a long jog.

Slowly but surely, training wasn’t something I simply liked to do. It was something I needed to do.

So now I was at a point where I a) was training every day and b)I finally had some semblance of exercise programming - rotating types of movement to actually have some chance of meaningfully improving.

Sessions a week: 7, religiously.

Total time training a week: 7-9 hours.

The new schedule worked. I made progress:

Early 2018. 80kg

Enter Fasting, stage left

This was also around the time I started becoming more interested in nutrition. I became vegetarian and was beginning to play around with time-restricted eating protocols like intermittent fasting.

In my pursuit of the one-arm chin-up, I was scared to put on weight. By looking at athletes online that were my height, I found out I was generally heavier than they were when they were able to do a one-arm chin-up. Therefore, I concluded, the move was simply about achieving a better power-to weight ratio. I figured I shouldn’t need to put on weight to achieve the move – I simply needed a higher ratio of muscle to fat.

Because of this, I methodically kept my weight the same - simply by not eating when it went up too much. This seemed logical to me as a way to go about body re-composition.

By all accounts, my physique and strength did improve. I became more muscular and defined and started to do things I couldn’t do before. Because I was improving, I didn’t think what I was doing could be in any way damaging, so I didn’t question it.

The downside to this improvement was that it only made me more psychologically dependent on exercising. Now if I missed a session I not only risked my emotional stability, but I risked losing this physical progress I had worked so hard to obtain. The perceived cost of not training rose week on week.

A case in point of this was in my planning of a trip to Venice. I was headed there for a week or so in December of 2017. Before going on this trip - when I realised there were no gyms in the reasonable vicinity of where I was to stay - I used google street maps to find, entirely in advance, a tree with a horizontal branch where I could hang gymnastic rings and train. I spent a good few hours scanning parks to find a few places that might work, as this way I wouldn’t have to waste time when I got there. I knew I’d be able to get my hit.

It did not occur to me that this was odd.

Incidentally, the tree I picked worked perfectly.

Tour - July 2018

Me during Tour, July 2018. I was not healthy here, dropping down to 76kg by my return

My progressed eventually plateaued. As I finished my degree, my holy exercise schedule was upended when I went on month-long improv tour in America.

I anticipated an emotionally intense time, and so knew that I would have to train daily to remain sane. My recent plateau in progress made me ever more panicky about missing a session, as I didn’t want to now start going backwards .

I found a gym that was a 15 minute jog away from the main place we were staying. When not on the road, I went there, regardless of what time we had returned from our performances the previous night. When we spent a few days away from base, I invented random workouts to satiate me. To compensate for a lack of a proper stable routine, I increased the length of my fasts.

During the month, I sustained 4 injuries. Running 30+ minutes a day to the gym with a heavy backpack resulted in me getting tendonitis in my left hamstring. I collapsed in a squat rack, squatting a weight I’d normally be fine with and ended up with sciatica on the right side of my lower back. Too many handstand pushups gave me a medial deltoid strain on my right shoulder. I was still relentless trying to get the one-arm chin-up, which resulted in me straining my left bicep.

Any one of these injuries should have been a big red flag to slow down and stop - but I trained through (not around) all of them. I kept running. I kept squatting. I had to.

To top this all off, I had great trouble sleeping more than 4 or 5 hours a night during the trip, which probably contributed to me getting injured.

So between the late nights, lack of sleep, lack of eating, excessive training and four injuries, I returned to the UK in a bad state. I had lost 4kg - dropping down to 76kg.

Despite all of this, I still didn’t stop. I took it as a challenge to push myself further.

August 2018 - January 2019

Two months after returning from the tour, and having done a short show run at a festival in Edinburgh, I found myself working in Waterloo for a small software company. I began physical rehab, slowly building up my lifts and calisthenic moves again.

Unfortunately, finding myself once again in the world of work brought back anxiety from my previous experiences of corporate life. Naturally, I leaned on exercise more.

I found myself getting up at 5:45am every morning to get 80 minutes at the gym (mainly strength and mobility) before going into the office. Sometime I would go back at lunch. I had long sessions on Saturdays and Sundays too.

As part of my rehab, I took up a hardcore mobility training protocol called Kinstretch, which I’d squeeze in a session every week.

Bent-arm sessions were things like pullups, dips, bench press etc. Straight-arm were mostly static holds, back levers, front levers and so on. Legs were legs.

Sessions a week: 8-10

Total time training a week: 8-9 hours

And again - working harder, exercising more, seemed to produce unquestionable results. By the end of the year, I was basically back to full strength. I slowly moved back to my normal weight and felt generally much stronger than I had previously. My physique was good, my body was working, nothing could possibly be amiss.

September 2018, 77kg

October, 2018, 78kg

Below are a few clips from my training around this time, post-recovery. In order: 50kg chinups, a dodgy back lever, 45kg dips and 15 kg weighted pistols. The first three were all working sets, the last one just something I tried for fun.

January 2019 - March 2019

As I settled back into London, I became more frenetic and remained anxious. I started adding more things to my life as a way to try and drown this out.

Outside of my regular job, I was back doing improv shows with Hivemind (my London improv troupe).

I committed to helping two students learn maths/Further maths A-level within a year, which meant I was tutoring 8-10 hours a week.

I also ended up getting an art commission, as I had launched a website selling posters I designed in my spare time. I was trying to continue to write, having just completed a writing course with a favourite writer of mine. And, to top it all off, I started doing salsa 1-2 times a week (albeit intermittently).

Sessions a week: 7

Total time training a week: 8-9 hours and 0-4 hours of dancing a week.

This wasn’t enough. As part of the “more=more” mentality I was developing, I became increasingly hardcore (read as; obsessive) about fasting.

Fasting is beautiful for someone with obsessive tendencies, because a fast is a way of constantly feeling like you’re achieving something, without actually doing anything. If you’ve been fasting for 16 hours, then continue not to eat, each second you ignore your hunger you are continuing to accomplish something ever more “impressive”. Magic.

I went from 16 hour fasts to 18 hours daily. Soon after, I extended to 20 hour fasts. Weeks later, I was sprinkling in 24 hours every so often, eventually finally peaking out with 40 hours of fasting semi-regularly. That’s 40 hours of eating nothing and only drinking water or tea. Zero calories and nutrition intake. I did not alter my training schedule, continuing to knock out sometimes two intense sessions a day.

This had side effects - namely, binge eating. Continually starving myself meant that I became more and more obsessed with food. I would over-consume calories in the short windows of time I allowed myself to eat, which generally wrecked my body. I would train lethargically on an empty stomach, wait hours and hours after training to eat, eat too much, go to bed overly full, then do it all over again the next day. It was a viscous cycle - the longer I fasted, the more I overate, which meant the longer I felt I had to fast the next day to make up for it. This type of cycle is pretty characteristic of an eating disorder. This was hard to admit.

I was living with my family. My father, with whom I trained on weekends, told me he thought I was verging on an eating disorder. But I disregarded it. I thought he just didn’t understand. This was the equivalent of someone denying they are an alcoholic — the “I can quit anytime” line.

Partly because of my bingeing, between October of 2018 to February of 2019, I put on 5kg. Part of this was muscle from the heavy weights, but not all.

What broke this cycle for me was, surprisingly, my vanity. It was a particular photo that was taken of me during preparation for a photo-shoot I did with my Improv troupe. This photo is below:

83kg, after a long day at work with a lot of bingeing.

Now some may see this photo and say I don’t look bad - but for me, it was a stark realisation I had put on body fat. I genuinely felt ashamed, especially given how much I was obsessing over training and fasting. Clearly what I was doing just wasn’t good for me from a physical point of view.

So I decided to change tactics.

I knew from my general obsession with fitness that the best way to manage weight was to do what bodybuilders do - calorie count.

So I got a digital scale, and began systematically weighing and calorically measuring everything - everything - I ate. I quickly worked out what would put me in a caloric deficit, and meticulously recorded my weight every day.

March 2019 - June 2019

My experience of weighing out all my meals, and calorie counting, was initially extremely positive. I found it really liberating to know, and not guess, how much I should eat every day. It took the guilt away from eating food which I had developed while I became obsessed with fasting. Eating wasn’t a sign of weakness or lack of will. I had a target to hit each day and hitting it would be a victory.

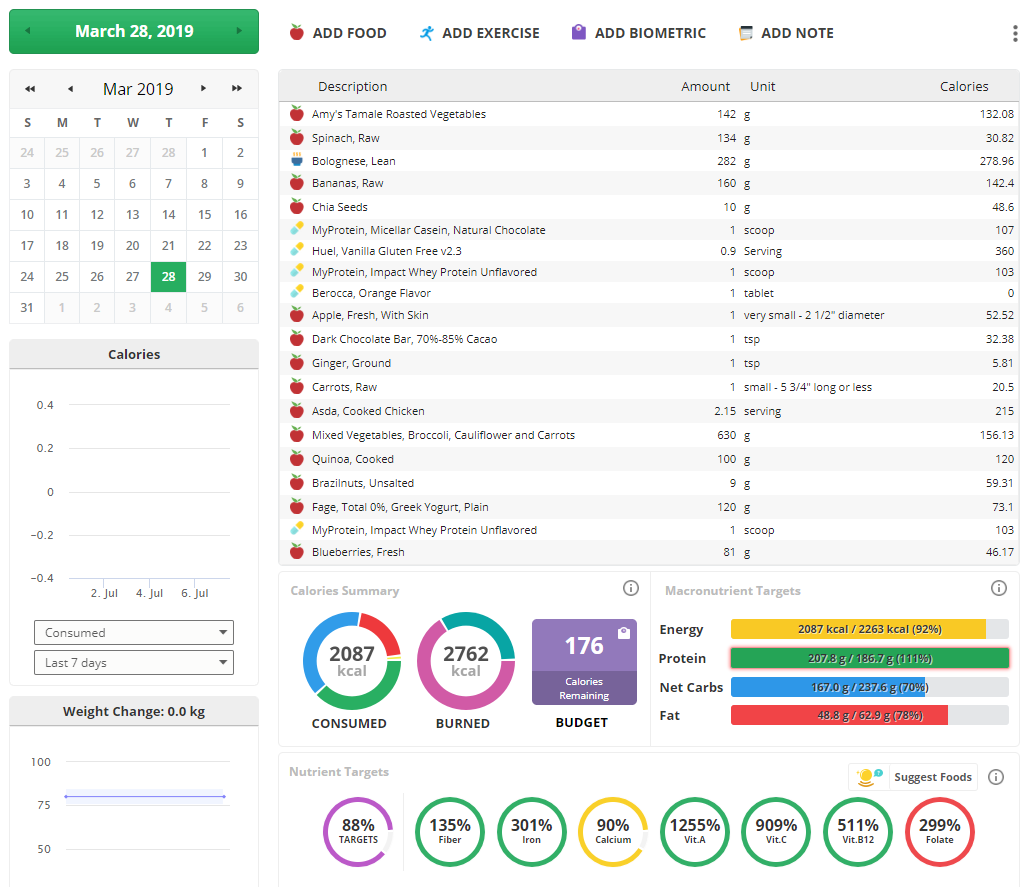

It also gave me a thing to nerd out on. A lot of people are familiar with MyFitnessPal as a way to do this, but I used Cronometer, which lets you look at macro and micronutrient breakdown:

Are you even on my folate level.

Of course, it didn’t take long before, this too, became an ugly behaviour.

Every time I looked at a food all I saw was its nutritional breakdown - and if I didn’t know it, I had to. I suddenly felt that I’d never be able to actually enjoy a meal again without thinking about how much of my daily budget it was using up. What was initially liberating - hitting a target every day - soon became a source of anxiety. How in god’s name did people manage to maintain their weight day-in-day-out without counting calories? The difference between being in a surplus and being in a deficit could literally be two slices of bread. It was maddening. I was cursed with knowledge about the apple.

As I was descending into this new obsession, I had an experience which was the beginning of how I broke through this noise of my anxiety and over-training. This experience was a weekend trip to train with the wonderful Online Movement University (OMU), which happened in March.

The OMU describes itself as the Netflix for physical education. It’s a wonderful community of people who genuinely just like to move and explore. They’re not obsessed with lifting the heaviest weight or being ripped - they’ve got a much more holistic view of health and fitness. I had joined their community for a single month in January, but decided to leave it as I literally didn’t have time to try out all the things they were exploring. I already felt like I was drowning and falling behind in the training that I needed to do to stay sane.

Thankfully, I took the plunge and went to actually meet some of them in Portugal.

For them, movement wasn’t a drug they abused, it was a genuine source of joy. Seeing how these people had a much better relationship with their bodies was the beginning of my realisation that I needed to reevaluate my relationship to training. It was also hard to deny that most of them could move far better than I and in more ways than I could, despite seemingly not being nearly as obsessive. What was I missing?

These guys were the best. I did murder, and was murdered by, some of them. But that’s another story.

I decided I needed to improve the variety of my movement diet. Still wanting to lose weight, I branched out to simply doing more kinds of training while keeping up with calorie counting. I started going jogging regularly again and I took up Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. I figured if I just moved more, and worried less about my strength, maybe I’d find pleasure in the variety. I even decided, after much consideration, to introduce a mandatory rest day.

Notice how I surreptitiously tricked myself into doing more training, despite this:

GPP = general physical preparedness. These sessions were sort of a mix of pushups, pullups, and sort of basic healthy movements.

Sessions a week: between 8 and 10.

Total time training a week: 8 to 11 hours.

Once again, by all appearances, this new combo seemed to work:

May 2019, two months of calorie counting, 81kg

June 2019, 80kg again. This was taken about a week before my blood tests showed I had extremely low testosterone. So… this isn’t even my final form.

I kept up with this routine for a few months and only stopped when I finally got my blood test results and, ultimately, my diagnosis.

I can’t help but wonder how I would have done on a blood/testosterone test at various different points in this journey. There were times when I was in a relationship and during those times I definitely expressed symptoms of someone with a high libido — but maybe it was below what it should have been. My best guess is that it’s only been in the past year or so, where the training volume and fasting become really obsessive (combined with a complete lack of decent recovery), that started to seriously damage my body.

But I can’t know for sure.

Had it not been for the blood test results, and subsequent MRI scan and general seriousness, I expect I’d still be going with the above schedule, or devising some new scheme to keep myself occupied.

Summary

I should say that the above is a simplified version of events. There’s a lot that went on in the in-between.

During this journey, I read an absurd amount of books, listened to a ridiculous amount of podcasts and generally over-consumed information on all topics related to health and fitness. I tracked every workout in some form or another - be it in a journal or online - for over three years.

I tried all manner of random exercises, routines, ‘superfoods’ and basically anything I thought would give me more insight on my body. I even went so far as to get analysis on my 23andMe data from a variety of different tools online to try and get a genetic insight into how I should be eating and training.

I’d fear the scale, and never liked what I saw. If I dropped weight I had lost muscle. If my weight went up I had put on fat.

I would routinely panic about not getting to bed early enough - as that would mean I would under-sleep, which would mean I wouldn’t be able to train as hard or recover as well, which would mean I wouldn’t get as much of a stabilising effect from exercise, which would mean I would slip back into feeling depressed again… and so on. I would often arrive home after work, exhausted, and lay on the floor for an hour, unable to move, before attending to whatever other tasks I had set myself.

I generally did my best to hide my habits without letting them interfere with whatever personal life I had. Making a session fit in was always my responsibility. For example, if I was to meet up with friends at 10am, I’d simply get up earlier and train then. Sometimes I’d get up as early as 5am to fit in a session.

Normally any nighttime social activity was out of the question. Late nights out with friends would disrupt sleep. Because of the aforementioned panic about sleep, I couldn’t afford to do that. Drinking was, of course, totally out of the question in all contexts, as it simply meant extra calories, worse sleep, and poorer performance.

My addiction to training - and eventually, my obsession with my eating, and body image — entirely dictated how I lived my life.

The diagnosis was the wake up call I needed. I was addicted.

My name is Jack, and I’m an exercise addict, with an eating disorder.

Analysis

Why did I do this, and why did it get so bad?

I’m not going to argue that my behaviour was rational. It clearly wasn’t - not for the purposes of either developing strength, combating depression or generally being healthy.

However, I can share how I rationalised it to myself. Consider the below:

Exercise is considered a healthy thing to do, which we generally don’t do enough of.

Training always made me feel good.

The more I trained, the better I felt, and the more my body improved.

Despite all of my conflicting protocols of fasting and not resting, I still got stronger.

Combine this with beliefs I held about myself and my body:

I am not naturally strong or athletic, I have to work harder than everyone else to get the same results

Willpower is developed by overcoming difficulty and would help me get through depression

The mixture of these observations and beliefs meant that rationalising my behaviour was easy. Sure, most people would say I was over-training and under-eating (or eating in a very dumb way) but I was still getting stronger - this meant that the rules were different for me.

What I also slowly came to realise was that the antidepressant effect I received from training wasn’t from the physiological rush of endorphins or general feeling of physical exertion. It was the mental achievement of overcoming my lethargy and excuses.

Don’t get me wrong - the feeling of having trained was enjoyable. Improving in strength is also a great experience. But these don’t compare at all to the experience of performing well despite feeling terrible.

In some sense, training while feeling horrible was actually more desirable to me.

If I trained while feeling awful, it meant I had overcome weakness. I had conquered myself, at least for that day, and achieved some level of self-mastery. It meant I, rather than my depression or anxiety, was in control.

Try doing a 90 minute strength session after not eating for 24 hours, having strength trained the 5 previous days. If you set a new personal record in those sorts of conditions, you feel mentally strong. When you’re depressed, and prone to depressive episodes, knowing you can do these things is reassuring - you’re capable and can keep going or even thrive, no matter how bad it gets.

I have to admit that another part of this, at times, was ego. Though most of the time I didn’t really care how much other people trained or how they ate (as I saw exercise as a thing I was dependent on) there were definitely occasions where I felt a sense of superiority compared with others. This was usually in terms of mental strength and discipline. I’d listen to a colleague complain about still being hungry after just having had their breakfast and think to myself “I haven’t eaten in 16 hours, and already trained for 80 minutes today” — and I would feel smug. Oh the irony.

Why didn’t I tone it down, ever?

I think partly the reason this got as bad as it did, without anyone noticing, is that working out out every day is generally seen as something admirable. People would tell me they respected me for it, or commented on how they wished they could do the same. Had my habit been something that is generally perceived as negative - such as drinking every day - I probably would have been forced to question my behaviour sooner.

In addition, training for me was a very personal, solo affair. I mostly worked out alone. I didn’t have any friends who were even remotely as interested in nutrition or fitness as I was. This meant that my mind was an echo chamber and I didn’t have anyone to tell me that what I was doing was probably dumb. My behaviour was rarely questioned.

The exception to this is my father - who is also fitness obsessed. But I was rarely transparent with him about my eating habits. This should have been another red flag to me.

And ultimately, the fitness people I find inspiring are those that do ridiculous feats. I’ve written before about athletes like Ross Edgeley - who swam around Great Britain by swimming for 6 hours then resting for 6 hours repeatedly for 157 days. Or Amelia Boone, whose mantra is “I’m not the strongest. I’m not the fastest. But I’m really good at suffering.”

Compared with what they have done, or how they train, I didn’t really feel I was all that hardcore.

Why did the test results convince me to re-evaluate?

Though obviously the testosterone thing was alarming, it was the wider health implications from the blood test that really shook me up.

Primarily it was the red/white blood cell count – you know, the things that literally keep you alive. Testosterone, beyond its obvious purpose, is involved in elevating mood and maintaining neurological health.

I had forever associated exercise with keeping me sane. If I was overdosing and by reducing it could make myself feel better, cutting back is a simple decision. But surprisingly hard to implement.

The Gonad Rehabilitation Programme (GRP)

Being addicted to exercise is, I imagine, more akin to suffering from workaholism than alcoholism, in that totally ceasing the activity you’re addicted to, and dependent upon, probably isn’t the solution. One still needs to look after their body, much like one still needs to work.

Given I know I have obsessive tendencies, how am I managing to cut back?

I’ve decided to channel my obsessive energy into becoming driven towards recovering really well. I’ve stopped tracking weights and recording my workouts, at least for now, taking something of a ‘no season’ inspired by Jujimufu

Instead, I’ve started tracking recovery measures. I’ve recognised that the idea of “what gets measured gets managed” applies very strongly to me. I’m now routinely recording things like resting heart rate, and Heart-Rate-Variability (HRV), the latter of which is a reliable measure of how relaxed/stressed you are. For the foreseeable future, I’ll be getting regular blood-work done, which is another measure I can ‘succeed’ at.

I’ve also made peace with putting on weight. I may lose my abs, but that’s no big deal - I’d rather have, you know, functioning blood.

I’m still applying rigid discipline as , if anything, discipline has never been more important for me. I now need the discipline to do less rather than more. Even learning to switch off takes an act of self-will.

Ultimately, I’m learning to trust and be kind to myself again. I know I can take punishment - not eat, not sleep, and still train well, weeks on end. I know I have the self-reliance to get stuff done. I don’t need to prove to myself I’m not weak anymore - at least, not in this self-destructive way. I’m seeing being strong as actually recovering, rather than feeding my ego and insecurities.

Though the blood test was the 10-tonne weight that broke the camel’s back, lots of people slowly nudged me to a better place along the way. Besides my father, who’s a rock for me in life generally, Chris Odle, Lisa Weinhaus, and the top dogs at OMU Jon Yuen, DJ Murakami and Jon ‘Windmaster’ Mirth - conversations and general influence from these guys were instrumental in me taking a good hard look at myself, whether they realised it or not.

Thank you.

Another positive influence which has helped me stopped counting calories/not worry about fasting, is the fitness YouTuber Stephanie Buttermore, who has experienced the female variant of this condition Hypothalamic Amenorrhea. She’s got a video which I’ll link below. I’m basically embracing her idea of going ‘all-in’ - simply following my hunger and intuition when it comes to food and not worrying about it.

Lessons/Takeaways/Questionable Advice

My behaviour was the result of a lot of underlying issues. Depression, fear of being weak in body and mind, an obsession with health and becoming generally better. As such, the way I see it is there’s two sides to it - the behaviour of exercise addiction/fasting obsession and the psychological issues of being dependant on a behaviour to combat depression/prove you aren’t weak.

The former might manifest due to different psychological reasons and the latter might produce different behaviours.

I’m certainly no doctor or therapist. If you think you have depression or an eating disorder, please seek help -reach out to someone qualified. There’s lots of information and support out there, and these problems are widely recognised.

What I don’t think is widely recognised - and is perhaps often glorified - is an unhealthy relationship with exercise as a way to prove your discipline, mettle and general self worth.

Despite what the no-pain-no-gain crowd say, you’ve got to find your own balance.

Ask yourself this question - what are you trying to prove? Is your need to prove you’re not weak your greatest weakness?

Are you training as a way to enhance living? Or are you living to train?

If you’re an athlete, the latter is probably true, but if it resonates with anyone else, it might be worth pause and consideration.

What represents balance for one person may be not be balanced for another. Such is life. You’ve got to be your own master and judge. When it comes to the path to health, fitness and pushing ourselves, striving for these positive outcomes means we can easily miss when the behaviours become damaging.

Only you can truly self-assess what you’re doing, and whether it’s net benefiting you and your life. As Richard Feynman once said:

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.”

If you have any questions, or want to talk about this privately with me because some of it echoes your experience, or you’re just curious, please don’t hesitate to do so.